Supercold temperatures no stranger to Alaskan veterans

This was the temperature in Galena the morning of Jan. 19, 2017, but it’s nothing compared to what it was in 1989.

January 20, 2017

School was disrupted by cold temperatures on Jan. 19, with GILA students unable to reach classes on the SHS campus, but it could have been worse.

In 1989, the state suffered through a record freeze, with the official temperature in Galena at 70 below and many people reporting much colder temperatures. The Hawk Highlights staff asked people who lived through that cold snap to share their stories of how they survived the bitter weather.

Freda Beasley

The year was 1989 and all around the Interior Alaska the temperature was dropping.

Mrs. Freda Beasley, 39, was in McGrath when the cold snap of 1989 happened. She lived with her husband and two children in a house filled with lumber that prevented the cold from seeping into the toasty, warm house. She described the sky as “a heavy ice fog over the village.”

During the cold snap, the temperature was 60 to 80 below, which was hazardous to your health if you stepped outside a building poorly dressed because frostbite formed on any exposed skin.

Even nature was different during the cold snap, she said, such as the birds. For some reason, they were not flying around in the sky as they usually did.

While the weather outside was bitterly cold, her family would read, watch television, and do the daily chores. Occasionally she would allow her kids to go out and play, but only for a short period. They would also listen to the radio for any signs of the weather lifting.

Mrs. Beasley was taking long-distance college classes to attain her teaching degree at the time.

She said that the cold snap, in her village, lasted a whole month.

Fortunately, no they did not have any food shortages thanks to MarkAir, which “used to fly in to bring supplies for the village,” and “the majority of us had lived off the land.”

Mrs. Beasley said that the community were all well taken care of. The different ways that they avoided to cold included keeping the wood stove burning continuously, making sure that they did not have any possibilities of a chimney fire, and that they “made sure that [they] wrapped the propane tank in a sleeping bag, and housed it in a small, little house that enclosed the propane tank totally.” They had used a propane stove for cooking their food.

Mrs. Beasley also made sure that she was dressed in her Eddie Bauer goose down clothing, which had matching snow pants. She had stated there everyone else dressed the same, all bundled up.

Her and her sister had lost 18 pounds by the end of the month because they would walk to work bundled up.

The family had a trip planned to go to California to visit Disneyland. When they got to San Diego, it was 89 degrees – a difference of 178 degrees from back home. She said that it felt nice at first, being warm and all, until they got used to the heat. It was then that they got exhausted from the heat. Her youngest son started crying, saying that he was too hot.

They also rented two elephants to ride. She described the experience as “a cool breeze.” After, they went back to their hotel and soon her “little Alaskan Native kids” were swimming in the swimming pool.

She stated that people were looking oddly at them because nobody else was swimming, and that they considered it wintertime although it was very hot. Her two sons had a blast in the water though. She had said that, “(they) were just happy that it was over, that was a long cold snap.”

Reported by Veronica Beans

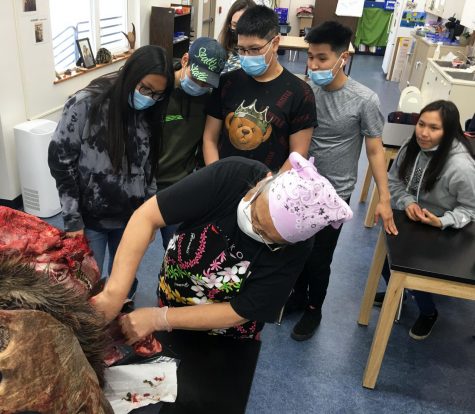

Freda Beasley, the cultural arts teacher at the SHS campus, was one of the many people impacted by the cold snap of 1989.

Mrs. Beasley and her family were in McGrath. The temperature in McGrath went down to 89 degrees below zero. The first thought she said came to her mind was, “I’m going to die! I was afraid I was going to have a hard time breathing because there was an ice fog all over. The cabin fire smoke was mixed in the fog and it hovered right at face level.”

Because of the extreme conditions, life had to be treated a bit differently.

“You couldn’t do any outdoor activities. We played table games, I baked with my kids and we watched movies. I was also taking college courses online so I definitely got homework done,” she said.

She also said there was no air travel, except for once a week, when Mark Air would fly to McGrath with supplies. “My family was well prepared,” adding they had plenty of food and enough wood to last for a few months if they had to.

One of the things that was hard about life in the cold was getting to where you needed to be. There were some people with garages for their cars, but the people who didn’t have working vehicles were given rides by people who had running vehicles.

Mrs. Beasley said that her most memorable moment was when she and her sister would dress up in warm clothes and walk to work, one or two miles, from Monday through Friday. “We made sure we had a buddy system so no one would get in trouble,” she said.

The exertion of walking and breathing in the cold, frigid air while wearing warm gear helped her and her sister unintentionally lose weight, she said.

“I wasn’t afraid of frostbite thought because I dressed warm enough with everything covered except my eyes. We would pull our parka’s ruffs forward to help us breath.”

Her most memorable moment involved the birds of McGrath. “When my husband would be walking from work he would usually see chickadees land on the willows, but during the cold, he saw frozen chickadees on the road. One day he was walking home, and he found a camp robber hanging upside down because it froze.”

She is now 66, but can still remember that frigid weather like it was yesterday.

Reported by Amanda Kopp

“It was very intense, had to make sure your body was cover,” said Freda Beasley, the cultural arts teacher at the SHS campus, about her experience in the 1989 cold snap. She was 35 years old and living in McGrath.

She said it was too cold to do anything.

“We had to be very diligent about making sure that our water didn’t get frozen, we kept our propane tank in a little building and we rapped a sleeping bag around it,” she said. “We made sure our water was always running if there was danger of it freezing up, and we also had heating tapes and constant checking of our wood stoves making sure the pipes were clean, because they were always running.”

Ms. Beasley said at her place in McGrath, Alaska, it was 80 to 89 below. She did not like the cold. The residents of McGrath did not use any vehicles expect the few that were kept running in garages in case of emergencies. The winter of 1989 is not a winter to forget.

Reported by Brenden Fuson

Freda Beasley experienced the cold snap in McGrath, Alaska in 1989, twenty-eight years ago. Mrs. Beasley lived in McGrath at the time the massive cold air had swept through Alaska with excruciating cold temperatures. The thermometer outside Mrs. Beasley’s house had measured negative eighty-nine degrees, staying in and bundled up as warm as possible.

Before leaving the house, they covered every exposed skin that is liable to get immediate frost bites and bundling their heads with fur hats. Freda met with her sister every morning on the month of January at 7-7:30 a.m. and walked two and half miles bundled up with fur clothing. Walking every morning of the day at cold temperatures and bundled up, they had lost 17 to 18 pounds. With cold temperatures outside and throughout Alaska, Mrs. Beasley “was fine with it, I made sure my family was safe and I didn’t let the boys stay out long.” To stay warm they had gathered woods to burn in the woodstove, she said.

Reported by Chris Semaken

Mary Edwin

The cold is one of the harshest elements in Alaska, and the cold snap of 1989 had near record-breaking temperatures that reached close to 80 below. Mary Edwin, who then lived in McGrath with her five children, has her own story about her battle with the frost.

In 1989, McGrath’s official lowest temperature that had been record was 75 below, but many reported having temperatures around 80 below on their thermometers. The harsh climate caused many difficulties in the family’s day-to-day life.

“The little oil stove would not work because the oil gelled up. Someone had to stay home to keep making fire. I worked at the school district office and no vehicles would start, so it was walk to work,” said Ms. Edwin.

The family had no running water at the time, so they did not have to worry about their pipes freezing. Rather they had to worry about leaving their home to haul water with their sled since no vehicles were working.

When leaving their house, Mary recalls wearing as many layers as she could find. Her attempts to avoid freezing were often in vain. “My eyelashes literally froze together, so it was hard to see. The goal was to expose no skin. It felt like skin would crack on the parts of my face that weren’t really well covered,” she said.

“It felt like I was always bundling up,” recalled Ms. Edwin’s daughter Stephanie, who was 7 years old at the time.

Luckily, that was not the first time Ms. Edwin had experienced temperatures below -55 F, so she was prepared to combat the cold snap in 1989.

“That was maybe the coldest I have experienced, but it was not the first time I saw -70 or lower,” she said.

Her past adventures with winter weather included breaking a fan belt on her car while driving on the Alaska Highway, arriving to Alaska dressed for a Christmas party at 70 below, and being snowed in at Huslia when she was supposed to fly to Fairbanks and give birth to her child.

Reported by Angelica Firmin

Elaine Settle

Even though it was 80 below zero during the cold snap of 1989, kids still went to school, people still went to work, and no one in Galena was hurt.

Elaine Settle, now 59 years old, can recall some of the days that occurred during the unordinary cold snap. During the winter of 1989, Ms. Settle was 32. It was the same year when she moved into Galena.

“Every day the temperature just kept dropping, it was very difficult to breathe outside, it lasted for a good three weeks,” Ms. Settle said.

She lived in a rental home near Sweetsir’s store, and she said that it was a very good rental; no major maintenance had to occur. Although, she said that later into the cold snap, the water was not draining down the pipes.

Ms. Settle worked at the clinic. She noted that there were no fatal emergencies due to the extreme cold.

Despite how cold it was, there was still school, and the people still had to go to work. She had to walk to work, though. She said, though, that there were many difficulties around Galena, including staying warm and dealing with no air transportation or ground transportation within the city because the vehicles would be at risk for permanent damage.

After the days of the temperature progressively decreasing, there was relief. “Once it finally got to fifty below, people finally started running around town in their vehicles, at that time fifty below felt warm,” said Ms. Settle.

When the topic of this year’s cold snap arriving started, it scared her. So she and her family got prepared, they got water, emptied their sewer and checked how much fuel they currently had. From her experience, she wants to advise community members to “stock up on food and water, and empty sewer, if you have heating tape, plug it in, and if you have a wood stove, stock up on wood.”

Reported by Evan Charlie and Elena Jacobs

Mathew Barkdal

The furious cold snap of January 1989 engulfed Alaska’s interior, leaving everyone and everything cold to the bone.

Mathew Barkdal, my grandfather, had just turned 25 and had just married my grandmother the previous October.

When the cold snap had arrived in Fairbanks, “54 below was the coldest I saw,” he said. “It stayed between 40 and 50 below for at least 5 days.”

The cold had made Alaska life a bit tougher. The hardest part of the experience during a 52-below day was “getting vehicles started,” he said. At the time, my grandfather remembers one morning his truck was the only one that started. Five other people asked for jump-starts.

“We got one of the others to start and I gave one lady a ride to her work.”

Having to get up from your warm house to work outside was a struggle.

“Since an ungloved hand would freeze instantly against metal it was too painful. Boots would get stiff and it would take 20 minutes to bundle up just to work out side for five to 10 minutes,” he said.

Vision was also a concern, as people were not able to see anything around them. “The ice fog was extremely thick. We lived in a U-shaped complex and I could not see the other side, just blurred lights,” he said.

Reported by Anthony Lyon

Charlene Askoar

Charlene Askoar from Russian Mission was 14 at the time of the 1989 cold snap in Alaska. She was not expecting to have been kept inside for two weeks that winter.

The temperature in Russian Mission held steady around -30 degrees on average, with -45 at the very coldest. Nothing seemed to have been too different about this winter, she said, other than concerned parents keeping their children inside. School continued, so did flights, and there was nothing abnormal toward the village, other than its ghostly appearance from housebound children.

When asked what she remembered Charlene answered, “Just the cold.”

Although the rest of Alaska seemed to have a hard time trying to stay warm in 1989, Russian Mission seems as if it has not had a hard time with the weather.

Reported by Kat Wilde

Boomer Bryant

In 1989, a cold snap in Alaska broke all records. At the time, Boomer Bryant was a senior at Galena’s high school.

She remembers everyone keeping their kids at home, except for her parents. Then school was cancelled for two weeks, her cats’ tails were freezing and falling off, people were running out of wood, fuel oil was gelling, and plastic shattered like glass.

“The first week of January was just like this year,” Ms. Bryant said. The first week or two of January was about 30 above and then it rapidly dropped to about -30, just like this year. She remembers that many families had to move in with each other to conserve wood and heating fuel.

Her dad, Don Lowe, was one of the few people who were able to keep their vehicles running.

She remembers him making her go to school even though it was -60. Bryant says she arrived at school and the building was so cold that she sat in the library with all her winter gear on until a staff member called her parents and made her go home.

Reported by Tirzah Bryant

Kate Thurmond

Kate Thurmond was 26 years old in Galena at the time during the cold snap of January 1989.

It was 88 degrees below during one of those days.

She and her husband Ed were the parents of two young boys.

They were living in a log cabin.

Her most memorable moment happened in their truck. “We were on the town side of the dike, we were going and the wheel of our truck rolled right off it. Ed stopped the car slowly, got out with his friend, climbed over the dike to get the tire [and] tightly put the tire back on and took off.”

Another memory dealt with heating homes. “[People were] running out of wood, the Air Force was giving bundles of lumber to people if they wanted,” she said.

Reported by Kala Hendrickson